In late April 2024, Astribot published the above promotional video for the Astribot S1 and it quickly circulated as evidence of a step‑change in consumer robotics.

This post reviews the footage from a computer‑vision and systems perspective. Based on what is visible in the video, I believe the demo is materially misleading: key sequences appear staged, pre‑programmed, or post‑produced, and the platform shown is not currently credible as a safe autonomous system around humans.

Disclaimer: This review is based solely on the published promotional video and publicly visible hardware; I have no access to Astribot’s internal system, logs, or test conditions.

Deconstructing the Astribot S1 “Hello World” video

For a robot (such as what the Astribot S1 aspires to eventually become) to be able to interact with the real world, it requires a good understanding of the world around it. For this you need computer vision and a sensor stack which typically includes i) depth sensing for estimating world scale, ii) some standard cameras for intelligent identification of objects and surroundings (so-called object segmentation or instance segmentation), and iii) ideally some infrared sensors for boosting low light performance, and so on.

Why is that significant? Because by identifying what kinds of sensors the Astribot S1 has (and what their field of view is), we can predict the theoretical extent of its capabilities.

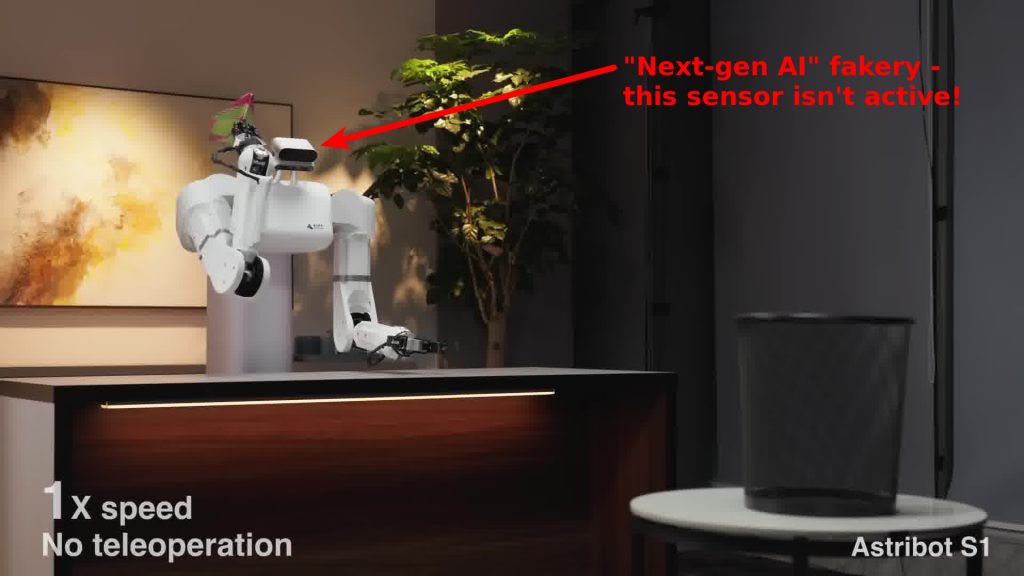

The robot only appears to have two sensor modules attached to it, both above the robot’s body.

- The top sensor looks very much like an Orbbec Femto Bolt – this off-the-shelf sensor package combines a high resolution RGB (colour) sensor and a Time of Flight (ToF) depth sensor.

- The sensor just below it looks like an Intel RealSense device of the D-family, possibly an Intel RealSense D415? (would need to see it up-close to say exactly which one it is – could for example also be a D455) – this would likely also carry one RGB (colour) sensor, and two infrared cameras for depth estimation.

Both sensors are pointed downwards, which will limit their ability to see very far, and especially the Intel RealSense-looking device can only be expected to see the immediate “table” area (its maximum vertical field of view or FOV would be unlikely to exceed 45 degrees). This materially limits safe operation in human environments in its present form – the robotic arms are powerful, and the potential field of view of the robot’s vision system is quite limited.

One additional point about these sensors is that it’s unusual for an actual product to integrate them in this kind of off-the-shelf form factor. Typically they would be integrated as modules (basically the PCB+sensors without the outer shell) into the product’s final design. The appearance of the Astribot S1 is consistent with a prototype-stage integration rather than a productionised design.

So, now that we have a hypothesis of the limited sensor capabilities of the robot as our starting point, let’s look at the video in a bit more detail.

Primary inconsistency: task execution outside observable field of view

One detail stands out throughout the footage: the sensor that resembles the Orbbec Femto Bolt does not appear to be active at any point in the video.

This matters because in at least one scene (paper plane thrown into a bin), the upper sensor is the only module that could plausibly cover the bin’s position from the robot’s perspective. If that sensor is not capturing, then the robot is executing that action without live perception of the target – consistent with a scripted or pre‑programmed sequence.

Why I believe the sensor is inactive: when the Femto Bolt is actively capturing, a small front‑panel activity LED is typically visible. No such LED is visible in any frame of the Astribot “Hello World” video. If the LED has been disabled in software or is otherwise not visible, that would be a meaningful detail to clarify since the video is presented as supposed evidence of autonomy.

Taken at face value, the footage repeatedly shows “next‑gen AI robot” behaviour without visible evidence that a primary forward-looking sensing component is operating.

Additional indicators

Other aspects in the video stand out as suspicious for a system which is supposedly capable of performing robustly in the real-world. Below are more examples:

Example 1: Non-robustly mounted sensors.

Take a close look at what happens to the sensors when the robot is moving quickly:

If you look closely at the cameras on top of the robot in the cup-sorting sequence, you will notice them exhibiting visible vibration whenever the robot arms are accelerating or decelerating quickly. This might be okay and perhaps acceptable for a first prototype, but this would be one of the first mechanical issues I would tackle if I were building machine vision for a robot like this! The sensor shaking causes a loss of accuracy due to motion blur, rolling shutter artifacts, and so on. Maybe fine for a crude first prototype of a robot, but not acceptable for a robot that’s designed for safe interactions with humans in the real world!

Example 2: The difficult steps are never shown in the video

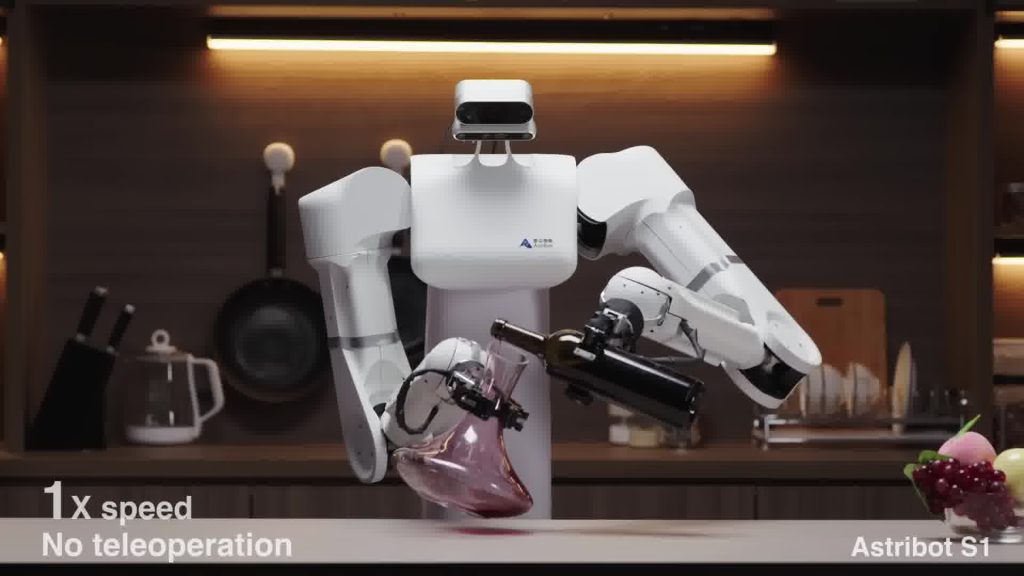

Another suspicious aspect is that the genuinely difficult computer vision tasks always happen off-camera. Take this scene with the glass decanter for example:

The scene starts with the robot already firmly holding the glass decanter, and there is no indication of how it got there without the robot accidentally crushing it! In this promotional video all the hard stuff happens off-camera, but the decanter shot is particularly suspicious because transparent objects would not typically register very well in the sensors that the robot is equipped with.

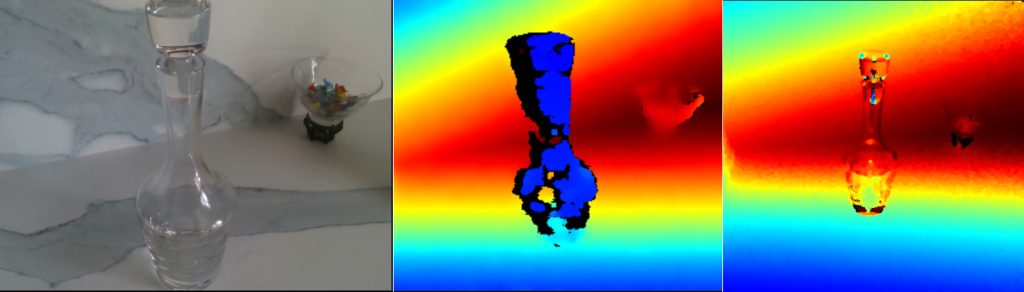

Although I can’t tell from the video exactly what sensor model is observing the table (I did speculate it potentially being a D415 or D455), the Intel RealSense family of sensors would regardless carry out depth estimation and mapping using one of two approaches: i) Time of Flight (often called ToF, sometimes LiDAR) which is used in the RealSense L-series, or ii) Stereoscopic depth, which is the method used in the RealSense D-series. Let’s quickly check what a glass object would look like in either type:

The depth map of a stereoscopic D-series RealSense can be seen in the center of the above 3 images. The colour gradients represent a range of distances. The black areas in the depth map image are undefined and contain no data at all, so for a sensor of this type the blotchy blue data would be all that’s visible of the carafe! On the right side we can see the depth map from the ToF-sensor of an L-series RealSense. With this sensing approach the carafe barely registers any depth at all – it looks like a ghostly magnification of the contours!

Astribot promises a +/- 0.03 mm precision for the robot, and this could well be true for the robotic arms (these are after all an off-the-shelf technology). But, in order for this kind of precision to be effectively applicable in an autonomous setting the CV sensing stack needs materially higher precision and robustness than commodity depth under the conditions shown.

A true test for the robot’s vision would be to present it with a variety of carafes, bottles and decanters of different thicknesses in random locations and observe if the robot can successfully and autonomously grab them all without dropping or crushing them. But, given there is no indication of sufficient vision capability existing in the robot I doubt we’ll see a real-world live demo of that kind anytime soon!

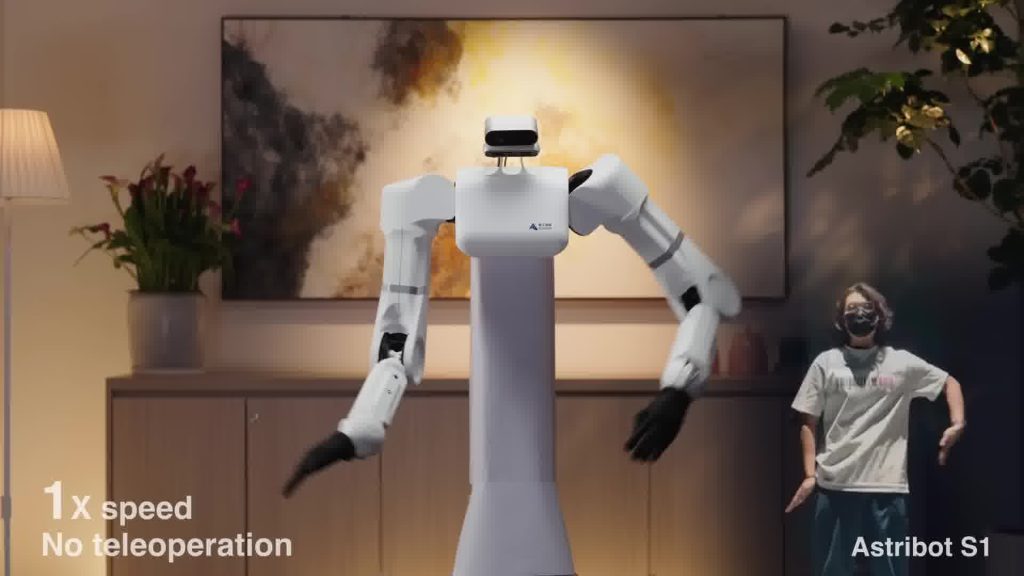

Example 3: The “no teleoperation” teleoperation demo.

The video includes a segment presented as “1x speed, no teleoperation,” showing a human motion overlay and the robot mirroring the movement. Based on the sensor evidence discussed earlier, this sequence is best explained as pre‑recorded motion capture and post‑production compositing, not a live autonomy demonstration.

In the clip there are a few interesting details which can help us deconstruct what we are actually seeing! In the above still frame, note how the hand orientation (roll) is not captured particularly accurately (compare the robot vs person hand roll!). If I had to speculate what was done (based on the little information we have) I would guess:

- The company appears to own an Orbbec Femto Bolt. It stands to reason the company would leverage off-the-shelf libraries available for the sensor (as that is typically the quickest way to get prototypes done quickly!)

- As it happens, Orbbec provides a software library called the Orbbec Body Tracking SDK . One of the limitations of this technology is that whilst the body tracking can reasonably estimate arm pose, it is less accurate in estimating hand rotation/roll!

- One cold engineering fact of building systems like this is latency. The Orbbec Femto Bolt sensor has a fair bit (80+ ms depending on imaging resolution!), and even the robot control interface would likely have some overhead. Although there are ways to mitigate latency in real-time systems, it is still interesting to note that there’s near-zero latency between the robot and the teleoperator in the video!

- Putting two and two together, my best guess for how this clip was created is that i) the operator sequence was pre-recorded with a Femto Bolt, ii) the body movements were converted into motion capture data using the Orbbec Body Tracking SDK, iii) this data was imported into the robot’s control software as a pre-recorded sequence – but with limited/missing hand roll data, and iv) the two separate takes were then combined in post-production to make it look like it was a real time “1x speed” event taking place. Again, misleading marketing at best!

Just to give you a sense of how much work it is to pull off something like I just described, a computer vision engineer with familiarity of how to program the robot (this can often take a few days of study!) could probably cobble together something like the above in a couple days of work. The end-result may look compelling, but it’s definitively not “Next-Gen AI Robot”!

Example 4: UI which is too fancy for what it is purporting to be.

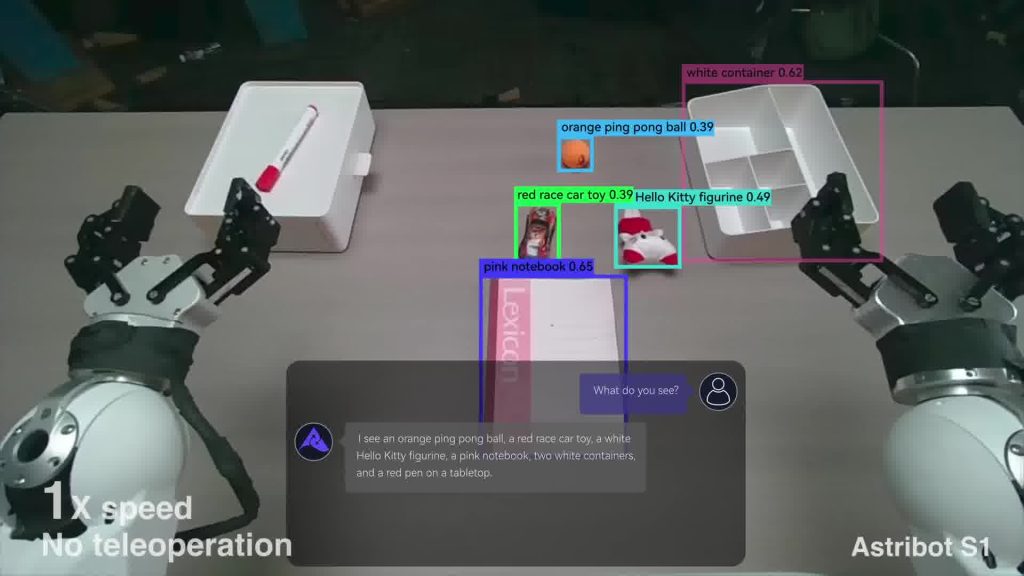

There is a sequence in the presentation which appears to be representing intelligent AI-like reasoning by the robot. The angle of the camera lines up with what I would expect to see through the Intel RealSense’s RGB (colour) sensor:

So-called object segmentation (which aims to identify classes of objects with some % of confidence) is a standard computer vision (machine learning) technique, and many powerful off-the-shelf libraries exist (such as the widely used YOLO model for basic object detection!). However, what caught my eye is that the sequence of events in the video doesn’t reflect real-world model behaviour. A few issues stand out:

- The classification is suspiciously specific, listing object classes such as “red race car toy” and “Hello Kitty figurine” – this is not how generic object classification is done! Training complexity increases for every class you add into your training set, and so in the real world the categories tend to be quite generic (think “airplane”, “car”, “van”, etc). For sub-class identifications other methods could be chained to the processing pipeline, but I see no indication of that having been done here!

- The segmentation results visually fade in step-by-step. This, again, is not how object segmentation works in the real world! When running neural network inference you get all the results at the same time.

- Building on the point of how oddly the segmentation results fade into the sequence (remember that this is supposed to be an “1x speed” capability demo!), the window at the bottom which is portraying an LLM chat dialog already seems to have the complete segmentation information in advance, before the results have even been registered on screen! Taken together, the timing and presentation are more consistent with an edited visualisation than with live inference output.

- Finally, if the inference really is as slow as it’s presented in this sequence, just imagine how terrifyingly dangerous the robot would be to any humans working around it! The robotic arms are fast (Astribot claims 10 m/s!) and strong enough to break human bones, which means that the robot would need to be able to reliably detect a human arm in its vicinity in 20 ms or even much less! Assuming that the Intel RealSense sensor in itself has latencies around 20 ms (several ms for frame exposure, a few for VPU depth etc processing, some for USB transmission, plus the OS overhead) , that doesn’t leave many milliseconds for running frame inference and halting a robot arm that is about to crush your sous chef’s hand!

In summary, this entire sequence looks like a post-production overlay animation (i.e. a CGI recreation) rather than a genuine version of what it is trying to present (such as a “1x speed” object segmentation model combined with an LLM exploiting the emergent capabilities of such a hybrid). It also strongly suggests that this robot – with its current sensor capabilities and latencies – couldn’t operate safely around humans!

Update (Late 2025): Open-vocabulary detection is now commodity. Models like OWLv2, Grounding DINO, and Florence-2 can identify “red race car toy” or “Hello Kitty figurine” out of the box with reasonable accuracy. The critique here wasn’t that fine-grained classification is impossible – it’s that this demo wasn’t actually running it, as evidenced by the staged fade-in and the pre-populated LLM dialog. The capability now exists; the question is always whether the demo is showing it live.

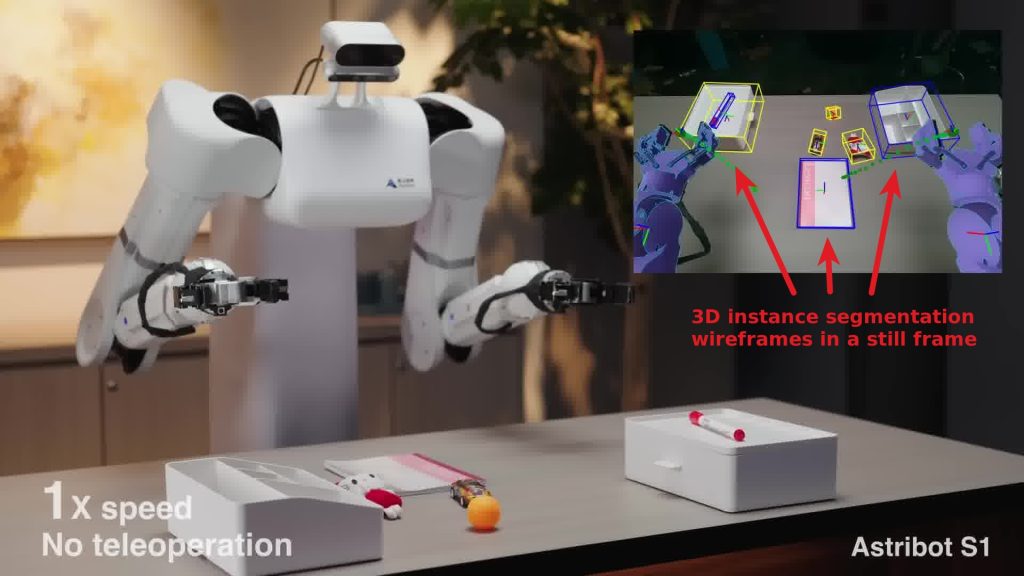

Example 5: Inexplicable loss of 3D instance segmentation capabilities

Continuing the theme of the video never showing anything genuinely difficult (computer vision-wise) happening on-camera, there is a part of the video where the robot is presented as being capable of generating a 3D instance segmentation map of diverse objects on the table, and then manipulating/organising these. One thing which strikes me as odd is that the instance segmentation results vanish from screen as soon as the robot starts to perform the sequence. Check the start frame:

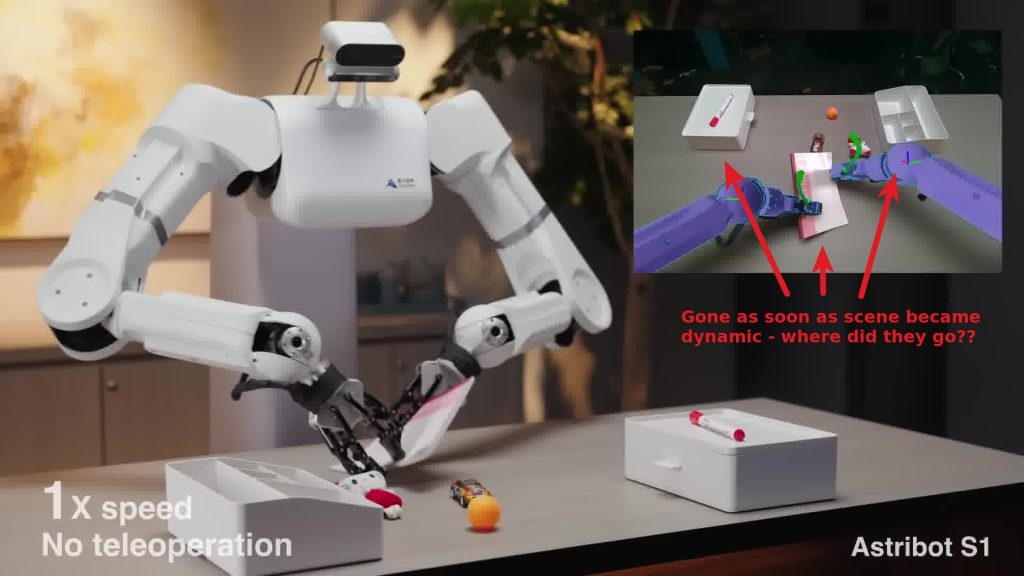

At first things look like expected, you can see 3D instance segmentation bounding boxes in the top right image above. But now see what happens when the robot starts to execute the sequence:

When the robot starts moving the 3D instance segmentation overlay vanishes! Is that because the sensor latency would make them misaligned? Is that because the robot struggles to accurately identify and delineate the objects mid-sequence? (And how would the robot interact safely and autonomously if so?) Or could it perhaps be that the company actually doesn’t have any robust 3D instance segmentation capabilities at all and that the initial wireframe presentation was simply overlaid in post-production?

Whatever the explanation is, given that other sequences in the S1 promotional video are (due to vision limitations) obviously pre-programmed, given that at least one part of the sensor stack (i.e. the Femto Bolt) is inactive the entire time, and given that the “Next-Gen AI Robot” capabilities presented even in this clip really do not show anything remarkable in terms of computer vision capability, I’m leaning towards assuming that even this seemingly impressive sequence is simply some painstakingly pre-programmed “AI theater” which is replayed enough times until the camera gets its “money shot” for the promotional video.

Update (Late 2025): The robotics landscape has evolved rapidly since this analysis. Vision-language-action models and improved sim-to-real transfer have made genuinely autonomous manipulation more feasible than it was in April 2024. Companies like Figure, 1X, and others have demonstrated more credible real-world capabilities. However, the core critique of this specific demo stands: the S1 video showed teleoperated or pre-programmed sequences, not autonomous operation, and the company’s sensor stack was demonstrably inadequate for what was claimed. The lesson – scrutinise demos for what’s actually running live versus staged – applies regardless of how capable the frontier has become.

Conclusion

For the kind of system portrayed in the Astribot S1 promotional video highly advanced and robust computer vision capabilities would be required in order for it to autonomously perform a diverse range of interactive tasks in the real world.

For such interactions to be safe around humans, the sensor latency and coverage would need to be substantially improved. A robot arm moving at 10 m/s is moving 10 mm (0.4 inches) per millisecond! A sensor like the Intel RealSense would typically run at 30-60 Hz for the kinds of resolutions shown in the video, which basically means that one video frame is captured every 33 milliseconds. How close to the (supposedly) autonomous robot would you be comfortable standing?

In summary, the most plausible interpretation of the footage is that the video presents pre‑programmed sequences and post‑production overlays as autonomous capability. The sensor coverage and latency implied by the visible hardware also do not support safe operation around humans at the speeds claimed.

If Astribot wants to substantiate its autonomy claims, the bar is straightforward: a continuous, uncut live demo with visible sensor status, timestamped raw feeds, and randomized object placement – showing perception and control closing the loop in real time.