Updated: 31 January 2026

Much of my career has revolved around growing engineering-led startups into self-sustaining organisations – without losing the thing that made them special: speed. This is a practitioner’s view of the technical transitions that define a company’s first few critical years.

The shifting technical landscape

In the 1980s and 90s, one-person software companies regularly shipped competitive products. Then technologies grew complex, tooling lagged, and team sizes ballooned.

Now small teams are back – not because software is simpler, but because universal tooling is stronger: cloud infrastructure as an API, AI-powered coding assistants, and foundation models you extend rather than build from scratch. When I first drafted this piece in 2024, I wrote about AI as a “force multiplier” for small teams. That framing already feels outdated. Today, teams not using AI tooling effectively are at a measurable disadvantage. The differentiator isn’t whether you use these tools, but how deeply they’re integrated into your workflow – and whether your team has developed the judgment to know when AI-generated code needs scrutiny versus when it’s trustworthy. The skill has shifted from “can you write this?” to “can you review this quickly and correctly?”

One sobering reflection while writing about my first production computer vision system – the Greyhound Tracking System of 2004 – was realising I could now build it for a fraction of the cost and time. What once required six months might now be six weeks, with a working prototype in six days.

The key ingredient for a tech startup is no longer problem-solving skill. It’s problem-solving velocity. If “Go big or go home” was yesterday’s mantra, mine is now: Go fast or go home. In 2004, your risk was running out of money before solving the problem. Today, the greater risk is becoming obsolete by the time you solve it.

Velocity, scaling, and risk

Startups can raise more money. They can’t raise more time.

Time compounds every risk: markets shift, competitors copy, platforms change, entropy wins – and it doesn’t even need a roadmap.

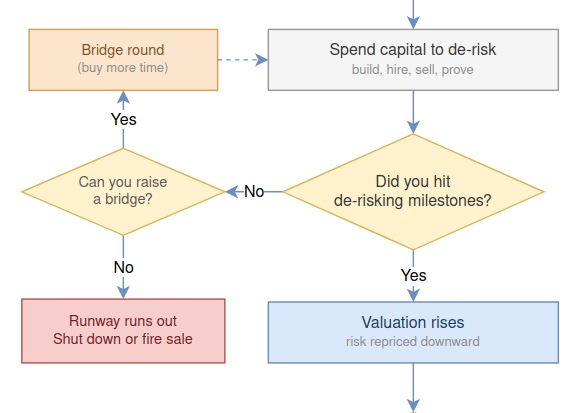

Whatever your startup vision, you must understand how much capital you need not just to build the idea, but to maintain high velocity while you de-risk it. For capital-heavy startups (hardware, electronics), the cycle is: reduce risk → increase velocity → scale → raise investment → demonstrate reduced risk. For lean operations (software-only), the loop is tighter: velocity comes from tooling and AI as force multipliers; income comes from customers long before it comes from investors.

At its core, valuation is a function of perceived risk. Every de-risking milestone – working prototype, first paying customer, validated unit economics – shifts the equation. The founders who understand this frame every decision through: what’s the fastest path to our next de-risking milestone?

Collapse the product feedback loop

Early velocity is mostly learning velocity. The fastest way to waste time is building the wrong thing efficiently.

A few operating rules that scale surprisingly well:

Ask the “2 weeks / 2 days / 2 hours” question. If you only had two weeks, what would you build to get signal? If you only had two days, what would you fake, simulate, or do manually to learn the same thing? And now: if you only had two hours, what throwaway prototype could you stub out with AI tooling to learn something this afternoon? This question kills scope creep before it starts.

Minimise hops to customer truth. How many people sit between a customer saying something true and your team acting on it? The moment you outsource discovery to “someone who will summarise it,” you insert delay into the loop. Delay is risk.

Pick a single wedge. If you can’t describe exactly who it’s for and why they’ll switch now, you don’t have product-market fit – you have optimism. Narrowing feels like going smaller, but it’s usually the fastest path to a de-risking milestone.

Treat the roadmap like a portfolio of bets. Most features are guesses dressed up as plans. Treat them that way: what’s the hypothesis, what’s the cheapest way to test it, and when do we walk away if the signal isn’t there? Teams lose months keeping “almost bets” alive because killing something you’ve invested in feels like failure. It isn’t – it’s the whole point of running cheap experiments.

Compound your learning rate – hire the right experience early

There’s a version of learning velocity that has nothing to do with build cycles or customer feedback loops. It’s about how much you extract from every interaction with partners, suppliers, and customers – and it compounds.

Consider a team entering a new domain – say, productising an embedded system for medical devices or industrial automation. Every partner meeting, every supplier visit, every technical review is dense with implicit information: scheduling signals, tolerance expectations, process maturity assumptions, regulatory posture. A veteran who has shipped products in that domain knows which questions to ask and when. They read the room differently. They hear what isn’t said. An inexperienced team sits in the same meeting and comes away with 60% of the signal. The experienced person gets 90%.

That 30% gap doesn’t just mean better meeting notes. It means the next set of decisions is better informed, which means the decisions after that start from a better position. Over 12-18 months, the compounding effect is enormous. The experienced team avoids dead ends that the inexperienced team won’t even recognise as dead ends until they’re six months deep. A wrong architectural choice made in month 3 because nobody asked the right question becomes a program-level setback by month 15.

This is counterintuitive for cash-constrained startups, because domain veterans are expensive and the ROI is invisible in the short term. You don’t see the dead ends you avoided. You only see the cost on the payroll. But if you’re entering a domain with long development cycles and high switching costs – hardware, automotive, regulated industries – the learning rate of your team in the first six months determines the trajectory of the entire program. Invest in it like the critical path item it is.

Scaling the engineering function

Flat organisations are perfect early, but they don’t scale. As complexity rises – product requirements, compliance, customer feature requests – you’re forced to add structure. The question isn’t whether, but how to do it without killing velocity.

Live ahead of the org. Whoever runs engineering should live six months ahead, anticipating roles to hire and problems to encounter. Technical leads should live two months ahead, translating strategy into concrete plans. Engineers can live one or two sprints ahead, focused on execution. This is why technical background is critical for engineering leadership – you need to see the curves coming. A non-technical leader simply can’t.

The Surgeon Model. A common mistake in specialist domains (CV/ML especially): teams hire only senior experts under headcount pressure. Everyone becomes a surgeon – who then spends their days on nursing, cleaning, and admin. Nobody feels fulfilled, and velocity collapses under essential-but-unglamorous work. Your expensive specialists end up with far less time for the problems only they can solve.

Build balanced teams instead. Rather than five expensive experts, consider three experts and two generalists. Your specialists stay happier, spending 80-90% of their time on the hard problems – and you give junior engineers room to grow into future leads.

That said, AI coding assistants have partially collapsed the surgeon/support distinction. Senior engineers with good AI tooling now handle tasks that previously required dedicated support – boilerplate, test scaffolding, documentation, routine refactors. This doesn’t eliminate the need for balanced teams, but it does mean a well-equipped specialist can maintain higher leverage for longer before the organisation needs to add junior support. The tradeoff is now less about headcount arithmetic and more about whether your seniors are actually using these tools effectively.

Right-size your teams. Fewer than five people isn’t really a team – if one person goes on vacation or gets sick, it has an outsized impact on delivery. More than ten creates too much cognitive load for a single lead. The pod model – small, cross-functional teams with clear missions, operating like mini-startups – scales remarkably well when done right.

Spot talent, don’t just reward output. The worst thing you can do is “reward” your best individual contributors with management roles they never wanted. Look instead for engineers who, with coaching, might make great leads – and give them that path deliberately.

Technical debt: the hidden tax

Not all debt is equal. Strategic debt is taken intentionally for short-term gain. Accidental debt results from lack of standards. Environmental debt emerges from infrastructure that made sense at one scale but not another.

There’s also a newer category worth naming: AI-generated drift. Code produced with AI assistance is often locally correct but globally inconsistent – the AI doesn’t remember the conventions you established three files ago. You end up with multiple implementations of the same utility, slight variations in error handling, architectural drift that only becomes visible when you zoom out. It’s not bad code, but it’s not coherent code either.

The danger zone is the MVP-to-mature-product transition. In MVP phase, taking on debt to move fast is strategic. As you scale, interest compounds. You’ve hit the wall when simple features take twice as long, engineers avoid certain code, and product teams ask why minor changes take weeks.

The solution: budget 10-20% of every sprint for maintenance. Focus on the key issues – the 20% of files causing 80% of your problems. And now, part of that budget should go toward consistency audits and consolidation of AI-generated sprawl.

The product transition

Many startups run founder-led for years. Then reality hits: feature requests explode, complexity exceeds what any individual can hold in their head.

That’s when product leadership becomes leverage – but the transition is dangerous. The “second-system effect” kicks in: teams overcorrect, over-engineer, and bloat the elegant thing that worked.

Make the transition gentle. The instinct is to professionalise everything at once – roadmap ceremonies, prioritisation frameworks, stakeholder alignment rituals. Resist it. Each layer of process adds latency, and latency kills the speed that got you here.

Keep engineering focused on the critical technical solvables, not the full backlog. And watch for the feature factory trap: when product leadership optimises for output (“ship these 12 features”) instead of outcomes (“move retention in this segment”), you’ll ship more and learn less.

When the world goes sideways, ship anyway

There’s a version of “go fast” that isn’t about competition at all. It’s about perseverance when the world around you turns heavy.

I learned that lesson the hard way in 2001. I was deep in startup life and in the middle of delivering a demanding project for a customer in the US. Then the World Trade Center was attacked.

Like everyone else, I watched it unfold in disbelief. And for the next two days I did what people now call doomscrolling – except back then it was just refreshing news sites over and over, as if the next reload would contain a different reality.

My client in the US was shaken too. They knew people affected. The mood was bleak. Nobody had the emotional bandwidth for “nice-to-haves”. Work felt irrelevant.

After about 48 hours, something clicked: I wasn’t helping anyone – least of all myself – by feeding the shock. I couldn’t change the news. I couldn’t reverse events. I couldn’t meaningfully improve the situation by staring at a screen. What I could do was one simple thing: I could control the quality of the next deliverable.

So I went back to work – not as denial, but as a way to regain agency. I focused on execution with almost stubborn intensity. Two weeks later I shipped the key milestone a week ahead of deadline, and at genuinely high quality.

I didn’t do it as a heroic gesture. I did it because I needed something concrete to hold onto. But the impact surprised me: it turned out to be the first piece of good news my customer had received in weeks. And when they communicated that delivery to their own biggest customer – a Fortune 100 company – it created a small but real positive ripple. It didn’t fix the world. But it helped a few people take a step forward.

That’s worth underlining, especially now, when the news cycle is infinite, personalised, and optimised for engagement rather than clarity: doomscrolling feels like awareness. It’s usually just unmanaged anxiety.

If you want a simple founder-grade protocol for “the world is on fire” days, this is mine:

- Check on your people first. Your team, your family, your key customers. A short human message beats performative productivity.

- Pick one concrete thing you can ship. A bug fix. A release. A customer deliverable. A hard conversation you’ve been avoiding. Something real.

- Set a news budget. Fifteen minutes in the morning, fifteen in the evening. Refreshing the feed is not an action plan.

- Execute like it matters – because it does. High-quality output creates momentum, and momentum is what gets teams through dark weeks.

- Communicate the win. Not as marketing. As signal: “we’re still here, we’re still moving, we’re still reliable.”

When things go wrong, founders have an instinct to absorb everything – every headline, every macro risk, every hypothetical future. But the company doesn’t need you to be a full-time consumer of bad news. It needs you to reduce uncertainty by delivering something solid.

On intensity and recovery

This article focuses heavily on speed and intensity – because in startups, these matter enormously. But intensity alone isn’t sustainable. Professional athletes understand something crucial: peak performance requires both hard training and strategic recovery.

I wrote about this balance in Things I Learned from Working with Professional Footballers, drawing lessons from years of building computer vision systems for elite sports. The principles translate directly to technical organisations: you need periods of intense focus, but you also need to know when to step back, reflect, and recover. Going fast doesn’t mean running yourself into the ground – it means managing your energy intelligently over the long term.

The path forward

The startups that win aren’t those with the cleanest code. They’re the ones that survive long enough to scale – treating technical debt like a financial instrument, building teams that balance expertise with execution, and maintaining the velocity that keeps them ahead of obsolescence.

You can’t raise more time. You can’t control the world. But you can control the next milestone.

Go fast or go home.