People ask me about startups more often than you’d think. Usually some version of: “Why does your company keep raising money? Are you… losing it?” And when they try to look it up themselves, they hit a wall of jargon – cap tables, preferential shares, vesting – that makes the whole thing feel like a secret club.

It doesn’t have to be. The answer to “are you losing it?” is: yes, deliberately! But to explain why, we need to talk about what “startup” actually means – because the word is overloaded.

Sometimes “startup” means two people, a laptop, and an obsessive desire to turn an idea into a product before the money runs out. Other times it means a company designed to scale fast enough that each funding round makes the previous one look cheap in hindsight. Both are valid. They’re just different machines – different models for powering a company to success – with different fuel, different constraints, and very different failure modes.

There are really two broad types of startups: bootstrapped and VC-funded. I’ve worked in both. The important part is not which category sounds cooler. It’s which one matches the reality of what you’re building.

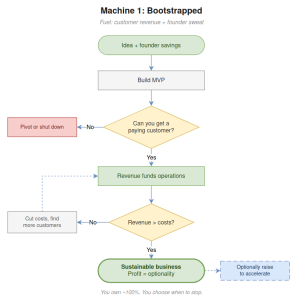

Machine 1: The bootstrapped startup

A bootstrapped startup funds itself from customer revenue and founder stubbornness. You sell something, you use the money to build more of it, and you repeat until you either have a real business or a very educational failure.

The canonical example is Mailchimp – never took VC money, sold to Intuit for $12 billion. Zoho is another: Sridhar Vembu has been unusually direct about why they never took outside capital. Basecamp built a profitable software company by the radical strategy of charging customers money and then keeping it.

Bootstrapping forces a certain discipline. You learn pricing early, because you have to. You feel customer churn in your bones, because it’s your rent money. You don’t get to hide behind “we’ll make money later once we’ve grown big enough.” There is no later – no “monetising in Series C.”

The tradeoffs are real: you’ll probably grow slower. If what you’re building is expensive before it earns anything – physical hardware, say, or a product that takes a year of meetings before an enterprise customer signs a contract – bootstrapping may simply not be an option. But you keep control, you keep optionality (i.e. the freedom to say no), and nobody – except for the odd armchair expert on the Internet who has never run a business – gets to tell you your company isn’t growing fast enough.

Machine 2: The VC-funded startup

A VC-funded startup sells equity to investors and uses that money to buy time, talent, and market position. This is most appropriate when your company is capital-intensive, when speed matters more than early efficiency, or when there’s a land-grab dynamic where being in second place means being irrelevant.

Here’s the part that confuses people: VC-funded startups aren’t “running out of money” in the way a failing restaurant runs out of money. They’re spending money on purpose, to prove things.

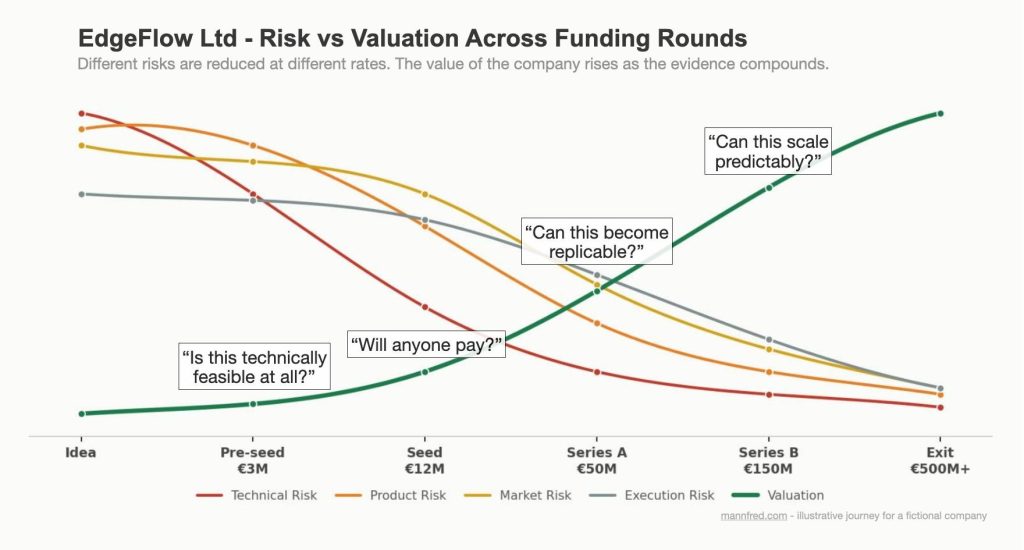

The core mechanic is what I call the de-risking ladder. Every funding round is the company saying: “Last time, these things were uncertain. Now they’re proven. Therefore we’re worth more.” Pre-seed round: does the technology work? Seed round: will anyone pay for it? Series A: can it repeat? Series B: can it scale?

This is the mental model most people are missing – VC funding isn’t just cash. It’s repricing risk. Each round converts existential questions into operational ones, and the company valuation rises accordingly.

The accompanying diagram shows the idealised lifecycle of a VC-funded startup. Reality is messier, of course. Bridge rounds sometimes exist to buy time while looking for a buyer for a failing business, not just to hit the next milestone. IPO-readiness usually involves practical requirements – governance, audit history, reporting discipline, and a credible profitability narrative – that take years to build. And an exit isn’t always the end: sometimes an acquisition is the best mechanism for funding the next phase of growth. But the core dynamic is still simple. Reduce risk, reprice, repeat.

In the classic playbook, VC-backed companies aim to raise roughly every 12 to 24 months – enough time to hit meaningful milestones, not so much that you run out of runway (i.e. money in the bank). But this isn’t fixed. Market conditions shift. Carta’s data shows the median time from Series A to B stretching to a record ~2.8 years as of Q1 2025, with bridge rounds (smaller interim funding to keep the lights on) increasingly common to extend runway between priced rounds.

So the modern version of the rule is: you still raise to de-risk, but the market decides how much evidence it demands before it rewards you.

In the VC-funded model there’s a cost beyond dilution. VC investors typically get board seats, and with them real influence over strategy, hiring, and when to raise again. Early on this can be genuinely helpful – good investors bring networks, pattern recognition, and a useful kind of pressure. But the dynamic shifts as the board grows. By Series B you may need board approval for decisions you used to make over coffee. The founder who once had full control becomes accountable to the board. This isn’t necessarily bad – accountability can sharpen decision-making – but it’s a fundamentally different way of running a company.

A concrete example – EdgeFlow Ltd

Let’s make this concrete. Imagine you and I founded EdgeFlow Ltd together – a fictional B2B company selling computer-vision quality inspection for factories. AI-powered edge inference, cloud analytics, the full stack – most of the correct buzzwords (can we fit ‘agentic’ in there somewhere?). It has both deep-tech risk (will it work in messy real-world environments?) and go-to-market risk (will factories buy it fast enough?). Since it’s a hardware business it will require a good amount of capital down the road, and we opt for the VC route.

Here’s roughly how the de-risking plays out for us:

Pre-seed (post-money valuation of €3M): The question we’re trying to answer at this stage is “Is this technically feasible at all?” That €3M is what investors think the whole company is worth right now – mostly a bet on the team and the idea, since nothing is proven yet. If all goes well, the company will have a prototype that works on real data, a credible team, and a clear market wedge. Founders own about two-thirds of the company. (For simplicity, this example ignores option pools and other cap table mechanics – the ownership figures are illustrative.)

Seed (company valued at €12M): “Will anyone pay for this, and does it actually work in the real world?” A few customers are now paying for pilot deployments. The system installs and runs reliably. There’s evidence it saves them money. Founders now end up at around 50% of total share ownership.

Series A (valuation now €50M): “Can this become a repeatable business?” The company can sell without the CEO personally closing every deal. Customers are paying recurring revenue – and renewing. The numbers actually work. Founders around 40%.

Series B (€150M valuation): “Can this scale predictably?” The company is expanding into new markets, customers are staying and buying more, and the business is profitable per unit sold. After selling equity for several rounds, founders now own only around a third of the company. (Some companies go on to raise Series C, D, and beyond – the ladder continues as long as there are milestones to hit and investors willing to fund them.)

Notice what changed between “high risk, low valuation” and “lower risk, higher valuation.” It wasn’t the pitch deck. It wasn’t the logo. It was the company’s probability-weighted future.

For a hardware-enabled company like EdgeFlow, the journey from Pre-seed to Series B typically takes four to six years – assuming things go well. Many companies take longer. Some never get past seed.

In our example, though, EdgeFlow does well. One by one, the big questions got answered. Technical risk? Answered – it works in the field, not just in the lab. Product risk? Answered – customers adopt it and get real value out of it. Market risk? Answered – budgets exist, timing is right, and procurement isn’t a dead end. Execution risk? Largely resolved – the team can hire staff, deliver product, and support customers repeatedly without everything depending on the founders doing it personally.

When investors say “this is lower risk now,” what they mean is: more of the future has become predictable. And predictability is what markets pay for.

So what do the investors get out of all this? They own shares in a company that’s becoming more valuable. Eventually, either the company gets acquired by a bigger company, or it lists on the stock market (an IPO). At that point, everyone’s shares have a real price tag and can be sold. If EdgeFlow exits at, say, €500M, the investors who bought in at a €3M valuation have done extremely well – and the founders’ remaining third is worth roughly €165M. Not a bad outcome for an idea that started as a big question mark. But not every startup gets there, which is why investors spread their money across many companies – and why the ones that do work need to work exceptionally well.

(NB: I’ve simplified the dynamics quite a lot here – in reality funding rounds involve cap tables, option pools, liquidation preferences, preferential shares, anti-dilution clauses, pre-money vs post-money valuations, and enough jargon to fill a textbook. If you’re curious about the actual mechanics there is plenty of information available online.)

Choosing the right machine

If you’re deciding between these paths, the honest questions are:

For bootstrapping – can you get to revenue fast enough to survive? Is your product sellable without massive up-front burn? Are you willing to grow slower in exchange for control?

For VC – does your market reward speed disproportionately? Is your startup capital-intensive by nature? Does it need to become very large to work at all?

And the question underneath all of those: are you building a company to be sustainable, or a company designed to be fundable? They can overlap – but if you’re being honest, you usually know which one you’re optimising for. And that choice will shape every decision you make for the next five to ten years.

If you’re not founding a startup but considering joining one, understanding which machine you’re stepping into matters just as much – but that’s a topic for another post.

The point

Funding isn’t the point – it’s the fuel system. Choose the wrong one, and you might still build something great. You just won’t be able to power the business that grows around it.

Whichever machine you choose though, speed is always critical. I’ve written more about why velocity matters – and how to maintain it as you scale – in Go Fast or Go Home – The Art of Scaling Technical Startups.

So the next time someone asks you why a startup keeps raising money, you’ll know: they’re not losing it. They’re buying answers to expensive questions. And the next time someone tells you a bootstrapped company “isn’t ambitious enough,” you’ll know they could use a lesson (such as this article) in how startups work!